Having lived in Lucknow for years, I never gave Sikandra Bagh much thought. But now, as a tourist in my hometown, I felt a poignant mix of nostalgia and discovery. This unplanned visit stemmed from a morning walk in the Botanical Garden across the road. What I stumbled upon was a hidden treasure of history and heroism.

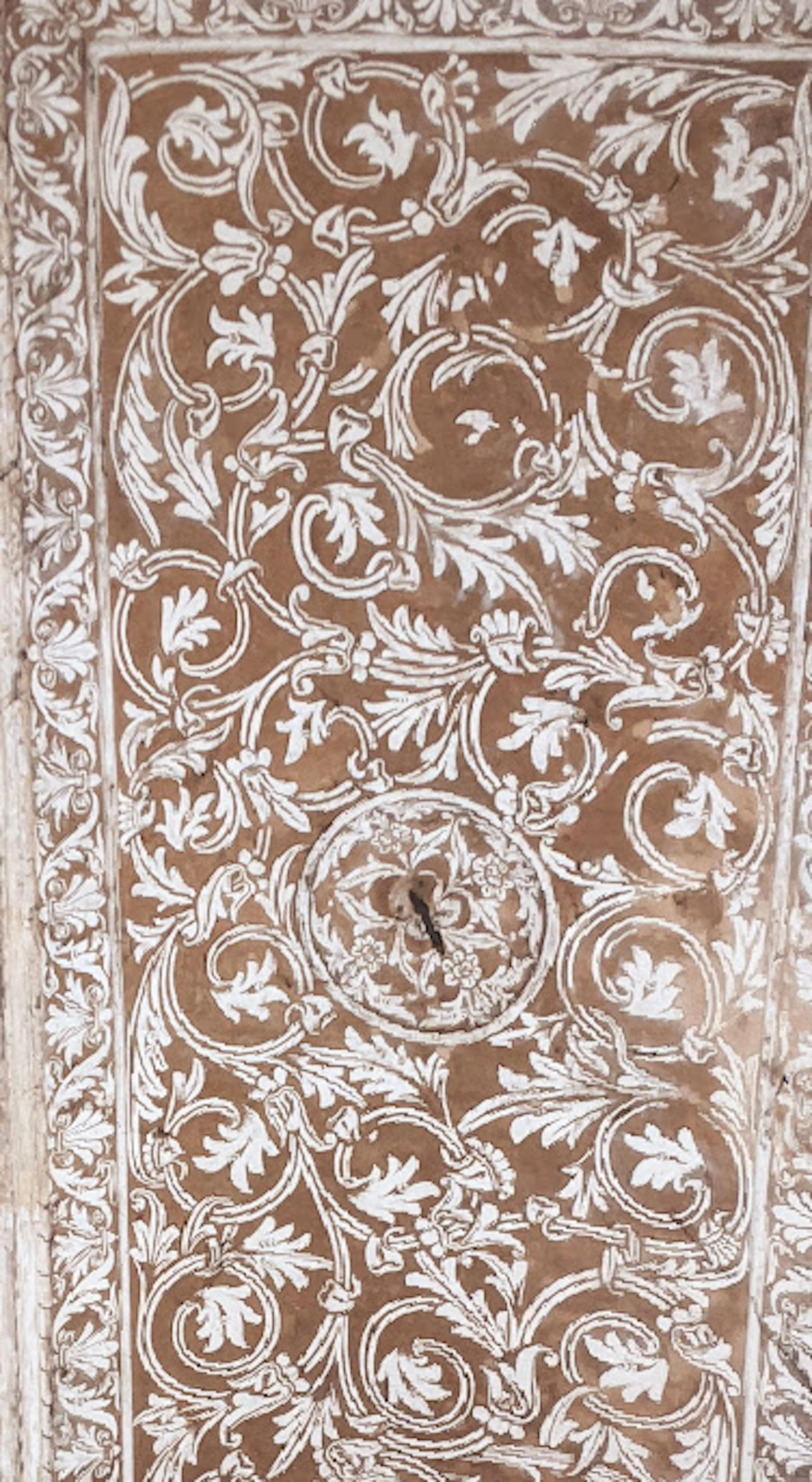

Sikandra Bagh, though modest today, whispers of a glorious past. It served as his summer retreat, built by the last Nawab of Awadh, Wajid Ali Shah (1847-1856). Imagine lush gardens flanking a three-towered palace complex, a vibrant Nawabi court. The unique “pair of fish” entrance hinted at Nawabi prosperity, while the architecture itself was a fascinating blend – Chinese pagodas, European arches, and Persian domes in beautiful harmony. Traces of delicate artwork and the lone remaining gateway adorned with Chikankari-like moldings spoke of the monument’s former grandeur.

Standing amidst these remnants, I envisioned Sikandra Bagh in its prime – a testament to Wajid Ali Shah‘s artistic tastes. But Sikandra Bagh‘s story goes beyond its beauty. Within its walls unfolded a fierce battle during the 1857 revolt against the British East India Company. Here, I encountered the tale of Uda Devi, Sikandra Bagh‘s unsung queen.

Uda Devi, born into a Dalit family, was far from royalty. Yet, her spirit burned with the fire of rebellion. Joining forces with Begum Hazrat Mahal, Wajid Ali Shah‘s wife, she formed and led a battalion of Dalit women. The battle at Sikandra Bagh on November 16, 1857, was brutal. Uda Devi‘s leadership and courage stunned the British commander, Colin Campbell. Legend has it that upon learning of her husband, a senior warrior, being martyred, her grief transformed into rage. Determined for revenge, she disguised herself and climbed a banyan tree overlooking the battlefield. Imagine the chaos – the rumble of cannons, the shouts of soldiers. Uda Devi, a lone sniper, picked off British soldiers with deadly accuracy. The sheer number of casualties inflicted by a single “sniper” speaks volumes of her bravery.

Sadly, her story ends tragically. Suspected by the British, she was shot and killed. Around 2,300 freedom fighters perished that day. Ironically, more Victoria Crosses were awarded for this single day than any other in the conflict, many for capturing Sikandra Bagh. Uda Devi, the “Unknown Warrior,” faded into history. A statue stands in her honor today, a reminder amidst the neglected Sikandra Bagh.

This visit left me with mixed emotions – pride in Lucknow’s history and regret for overlooking this gem. Uda Devi‘s story reminds us that heroism can emerge from anywhere. As a tourist in my city, I discovered a monument, a tale of courage, sacrifice, and rebellion. Sikandra Bagh awaits rediscovery, its whispers waiting to be heard. The next time you’re in Lucknow, take a moment to step into this hidden chapter of history. You might just be surprised by what you find.